Wish you could shoot shipwreck photos good enough to grace the pages of a dive magazine? Photo journalist Jason Brown reveals his ‘go to’ tricks to help you shoot better wreck photos.

The shipwrecks of the WW1 German High Seas fleet in Scapa Flow continue to be a popular destination for underwater photographers looking to get that ‘big gun’ shot. What is it about shipwrecks that makes them so fascinating? Maybe it’s the promise of lost treasure lurking deep with their holds or simply the surreal spectacle of exploring an object so alien to the marine environment that ended its life in such a dramatic and unexpected way.

For me, it’s something far simpler – it’s the history of the wreck and the promise of the stories that they can tell that fascinates me. Shipwrecks are far more than just scrap metal on the sea bed – they’re time capsules that tell a story of days gone by. Stories of maritime trade and adventure, the people that served and often died on them, and, of course, times of war and conflict between nations. Military wrecks are particularly fascinating as they often bore witness to some of history’s most dramatic events.

Of course shipwrecks also make great photographic subjects but, as many underwater photographers discover, shooting a decent wreck photo is a lot trickier than it may seem. Over the years I’ve been fortunate to dive and photograph shipwrecks across the globe and I’ve had more than my fair share of photographic failures. The mistakes we make can be our best teachers so never just discard them – instead, take time to look at what went wrong and think about how you could improve. It’ll be the first to admit that I’ve learnt some invaluable lessons from the many shots that didn’t quite go to plan. Below I present nine golden nuggets of painfully-learnt advice to help you develop your skills as an underwater wreck photographer…

TIP #1 GO WIDE!

Not convinced that a compact camera can shoot great wreck photos? This shot of BSA motorbikes inside the Thistlegorm was shot using a 15 year old 6-mpixel Canon compact camera!

It should be fairly obvious that a macro lens is perhaps not the best ‘weapon of choice’ to shoot great shipwreck images. By their very nature, shipwrecks tend to be very large subjects so choosing the right camera and lens combination is essential.

For best results, you want to use a digital SLR camera in a dedicated camera housing with an ultra-wide fisheye lens. A fisheye lens will give the widest possible field of view (FOV) which will allow you to cram as much of the wreck into the frame without having to be so far away from the subject that it becomes lost in the murk. Most modern DSLR cameras can produce superb results underwater but try to go for one with great low light capabilities – being able to shoot at high ISO with minimal noise is invaluable in darker conditions.

Compact camera users can shoot great wreck photos too. Several companies produce ancillary ‘wet’ lens that can be attached to the front of a compact camera housing to give a considerable increase in coverage – the Inon UFL-165AD, for example, will deliver a 165 degree field of view and can be mated with a range of different cameras with the appropriate mount adaptor.

TIP #2 – LEARN TO BALANCE LIGHT

The engine block and chassis of a Land Rover lies exposed just inside the holds of the wreck of the Aeolian Sky, UK.

One of the biggest challenges of shooting shipwrecks is lighting them – their sheer size is far beyond what even the most powerful strobe or video light can cover. The trick is to not attempt to light up the entire wreck – instead, learn to compliment artificial lighting from your strobes with ambient light. Once mastered, balancing the two types of lighting can be highly effective as it allows you to portray the scale of the wreck and draw the viewer’s eye to specific features on the wreck.

Shooting with ambient light does have a couple of disadvantages though. Firstly, you have no control over the direction of light – you cannot move the wreck and you certainly cannot move the sun so you’ll have to pick the right time of day to dive a particular wreck to get the light from the sun striking the wreck in the right place. Secondly, ambient light isn’t so easy to colour correct if you’re mixing it with light from your strobes – unless you’re shooting *very* close to the surface, white balancing for ambient and artificial light is nigh-on impossible – better to leave the ambient light as it is and colour correct the artificial light for best results.

TIP #3 – CRANK UP THE ISO

This image of the stern of the SMS Karlsruhe battlecruiser in Scapa Flow is a perfect example of what can be achieved by cranking up the low light capabilities of your camera. Shooting a wreck using ambient light requires some adjustment of camera settings to get the optimal exposure. In temperate waters like those found in the UK and most of Northern Europe, that means bumping up the ISO, particularly at depth. You need a decent shutter speed to get a sharp image so start by setting this at an acceptable level – say 1/60th of a second – and then adjust your ISO and aperture accordingly until you get an acceptable exposure without strobe light. If you’re shooting with a fisheye lens, depth of field is less of an issue so you can get away with using a relatively open aperture.

How far you can push your ISO is dependent on your model of camera – modern DSLRs offer very good low-light performance but noise will increase the higher you go. Typically, I try to avoid pushing ISO above ISO3200 on my Nikon but other cameras – the Sony A7 series, for example, offer even better high ISO performance.

TIP #4 – PORTRAY A SENSE OF SCALE!

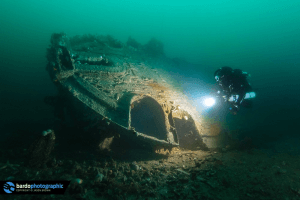

The great viz and strong ambient light in Malta makes capturing a shot of the entire wreck of the Bristol Beaufighter very easy indeed. Remember how you imagined a shipwreck when you were a kid? Most of us probably imagined an almost intact ship resting on the seabed with its masts still pointing towards the surface. Whilst the reality rarely matches this idealised image, some of the best wreck photos invoke these childhood memories by portraying a sense of sheer scale and recognition of the subject matter.

If you’re lucky enough to be shooting in an environment with almost endless visibility and lots of ambient light, back off and get as much of the wreck into the frame as visibility will allow. Images like this really are the money shot and are very popular in diving magazines. They are almost always illuminated entirely by ambient light only so shooting in RAW and fixing colour casts in post-production is a must if you want to reveal whatever limited colour is available in the shot. In darker, more temperate waters where visibility allows, you can achieve similar results by ramping up the ISO and strategically placing divers along the wreck to blast light towards key sections lost in shadow.

Such big shots aren’t always an option, of course, especially in more temperate waters where visibility may be more limited. Where visibility is limited, focus instead on signature features of the wreck to portray a similar (but naturally more limited) sense of scale and recognition.

TIP #5 – ALWAYS SHOOT IN RAW

What a difference a little post-processing can make! A before and after comparison of a RAW image file vs the final processed image. What camera mode do you shoot in? If you’re not already shooting in RAW then you’re really not getting the most out of your camera. RAW files contain far greater ‘bit depth’ and give the greatest scope for post-shot adjustment. If you want to shoot great wreck photos to rival the pros, you’ve got to shoot in RAW and learn how to use post-processing software like Adobe Lightroom. All professional underwater photographers shoot in RAW.

Shooting in RAW really comes into its own when shooting wreck photos as it’ll allow you to squeeze every last detail out of your images. Whether you’re pulling details out of the shadows or tweaking white balance to make those rusticles pop, a program like Adobe Lightroom will unlock a level of image quality and dynamic colour depth you’ll never achieve shooting jpegs.

TIP #6 – OFF-CAMERA LIGHTING

Off-camera lighting unlocks a whole new level of creativity. Here a strobe has been placed inside one of the barbettes that once held the massive main gun batteries of the German battleship SMS Konig.

If you really want to take your images to the next level, off-camera lighting is a great technique worth mastering. Instead of relying on ambient light to illuminate areas of the wreck that your camera strobes cannot reach, off-camera lighting allows you to illuminate background features using artificial light. It’s a great technique for ‘popping out’ areas of the background that you want the viewer to notice – a deck gun, for example – or for simply illuminating an area of a wreck that may be lost in shadow.

In some environments, off-camera lighting is a must. On deeper wrecks or those in more temperate waters, you may not have the luxury of strong ambient light – without off-camera lighting, much of the wreck maybe lost in the darkness. By strategically placing lights into the background of your shot, you can illuminate areas of the wreck that would normally be lost in the shadows. This technique works particularly well in silty environments as off-camera lighting doesn’t suffer from the same risk of backscatter as the strobes attached to your camera rig, allowing you to get creative without worrying about backscatter.

Off-camera lighting generally comes in two forms – big, powerful video lights or more conventional photographic strobes connected to an optical flash sensor. Video lights are the easiest to work with as they give immediate feedback and are often the best choice if you’re shooting deep wrecks where bottom time is at a premium. Strobes, however, produce more (and, in my opinion) better quality light but are trickier to set up. They also need to be used with an optical trigger that detects the flash from the strobes connected to your camera.

TIP #7 – USE BACK-LIGHTING

A diver dressed head to toe in black inside the dark confines of a wreck is never a good combination but back-lighting lets you overcome this.

If you’re shooting wreck photos with models then back lighting is another powerful technique that can really make your photos pop. In order to shoot a great image of a diver inside a wreck, you’ll want to separate the diver from the background. This is quite easy to do in clear, blue water but a lot trickier in an environment with very little ambient light. It’s even tricker when your model breaks the cardinal rule of photography – they dress all in black in a mostly dark environment!

To get around this problem, I will often attach a rear-firing strobe with an optical sensor to the back of my dive buddy. Kent Tooling here in the UK make a really useful little marine grade stainless plate with a 1” ball mount which you can strap to just about any rebreather or dive tank with a suitable cam band. The 1” ball mount lets you quickly and easily attach a strobe to the back of your diver. You then route the cable from the strobe forward so that the optical sensor that triggers the strobe is facing towards the camera.

Once connected up, the strobe attached to the model will fire light backwards illuminating anything behind the diver. This not only illuminates the area of the wreck in the background but also has the added benefit of ‘popping’ the diver out of the background. It only really works with strobes, however – if you want to use video lights, you’re better off getting the model to hand hold the light and simply point it backwards.

TIP #8 – USE MODELS

The twin rudders on the belly of the battleship SMS Markgraf in Scapa Flow, Scotland. Adding a diver gives an immediate sense of scale!

You always dive with a buddy, right? Well it’s time to put them to work by press-ganging them into being models!

Models really come into their own when shooting wrecks for a number of reasons. For starters, they’re great for adding a sense of scale to your shots. It can be difficult to judge the size of anything underwater so adding a diver into your shot gives the viewer something relatable – a baseline that they can use to judge the size of a wreck feature next to something that is a known quantity. In this case, a human being. Imagine shooting an image of a large prop. How big is it really? For the viewer, it’s difficult to judge without some baseline to work with. Stick a diver next to it, however, and its scale is immediately apparent!

Models can also be very useful for guiding the viewer to the area of interest you want them to focus on, particularly if they also happen to be using a powerful dive light. Inside the engine room of a shipwreck, for example, you might get your model to shine their torch on a set of dials or other detail that the viewer may not immediately notice. It’s important that the models themselves interact with the environment too – there’s nothing worse than a model that ignores their surroundings and simply looks directly at the camera!

Models also add interest to a shot as they give the viewer a connection to the photo. Photography is visual storytelling and a good photo feeds our natural curiosity - we’re drawn into any photo that has a diver in it which is why you’ll rarely see a shipwreck photo in a dive magazine that doesn’t feature a diver somewhere in the frame. Magazines understand the psychology of what images draw their readers in.

TIP #9 – DO YOUR RESEARCH

Gaining some level of understanding of the layout of a wreck will give you a good indication of what areas are worth focusing on.

We only have a limited time underwater so it’s important to do a little research before you giant stride off the back of the boat. It’s worth taking a little time getting familiar with the layout of the wreck so you know where the more interesting – and photogenic - parts of the vessel are located. If you’re unable to cover the entire wreck in a single dive, focus on the areas of the wreck that are unique or instantly recognisable and plan in advance how best to get the shots you want.

It’s also worth doing a Google image search to get a feel for the sort of images that other wreck photographers have captured of the wreck you plan to shoot. This will give you an insight into the prominent features of the wreck – what’s worth shooting, what others have missed and what’s best avoided. I often look at other photographers’ work and think about how I would shoot the same subject differently – even if it’s simply from a different angle or using different lighting. Never copy someone else’s photo – always aim to put your own spin on whatever you shoot. Even if you shoot from a similar angle, aim to improve on the original by bringing something fresh to the shot.

Written by Jason Brown

An experienced trimix rebreather and cave diver certified through Global Underwater Explorers, Jason Brown is an accomplished underwater photographer whose work has graced the pages – and covers – of numerous magazines across the globe. An experienced writer with over 30 years experience writing engaging features for a diverse range of publications, Jason now focuses his writing and photographic talents on his life aquatic.

When he’s not shooting eye-catching photos above and below water, Jason is actively involved in a number of high-profile dive industry events. He is one of the lead organisers of both the EUROTEK Advanced Diving Conference and the award-winning TEKCamp diving masterclass event – both held every two years in the UK. In more recent years, he’s been invited to give talks on underwater photography at a number of leading dive events. Most recently, he contributed a section on the wrecks of Scapa Flow to the book ‘Wild & Temperature Seas’ which is available to purchase through Amazon.

View more of Jason's photography work online at www.bardophotographic.co.uk and follow him on Instagram at www.instagram.com/bardophotographic.