“Change is inevitable. Change is constant.”

Benjamin Disraeli — 19th Century British Statesman

There’s a vintage TV comedy sketch by Monty Python called ‘The Four Yorkshiremen.’ You can check it out on YouTube, but the synopsis is simple. Four old guys dressed in dinner jackets and who look like they’ve made it, are talking about how tough they had it growing up. The conversation quickly escalates from pretentious to ridiculous as they try to outdo each other by exaggerating the challenges they overcame as kids. For example: “… We lived for three months in a brown paper bag in a septic tank. We used to have to get up at six o'clock in the morning, clean the bag, eat a crust of stale bread, go to work down mill for fourteen hours a day…” And so on.

The sketch winds up with Michael Palin’s character saying: “But you try and tell the young people today that... and they won't believe ya’.”

With all that in mind, things really were very different when Michael Menduno first coined a term “technical diving;” a phrase divers throw around these days without much thought. Back then, we really did — to coin a phrase — live in a shoebox in the middle of the road and walk barefoot uphill to school both ways in the rain and snow.

There was plenty of seat-of-the-pants thinking back then, and a lot of misinformation about how to end a dive in as good a shape or better than when it started. Things have obviously changed for the better. Well, mostly for the better. Nothing illuminates the change better than the situation with underwater lights. They are cheaper, more powerful, more reliable, smaller, and brighter.

And we’re spoiled for choice when searching for a high-performance scuba regulator, a sidemount harness, a closed-circuit rebreather, a drysuit that doesn’t leak, even “little” accessories such as DSMBs, reels, spools, and a waterproof notebook.

One of the most profound changes has to do with dive computers.

Divers of all sorts — from those who want to bimble about at six or seven metres for a half-hour, to members of expedition teams opening up new cave passages at great depths a couple of hours swim from daylight — have benefitted not just from new technology, but in huge part from a changed mindset.

Last week, a brand-new diver studying for her very first open-water certification, looked at me wide-eyed when I explained how recently PDCs (personal dive computers) have become a mainstream part of a diver’s basic kit.

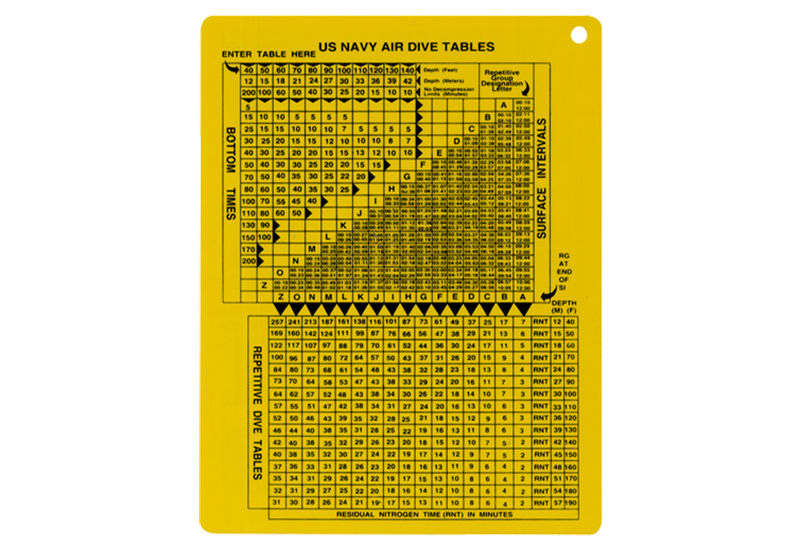

“What did you do before?” She asked completely puzzled by an old copy of a floppy plastic version of the US Navy Dive Table I’d handed to her.

And that got me thinking.

Once upon a time, I wrote an article entitled something like, “Dive computers have no place in technical diving.” Now that was long, long ago in a galaxy far, far away. Then, dive computers were designed by lawyers with an unwavering eye and tight, sweaty-palm grip on litigation; or more precisely, on avoiding it. And this fact alone made doing any decompression diving following the advice of a dive computer a real drag.

For example, on one notable occasion, after a moderate dive on a Canadian wreck sitting at a modest depth, the brand-new “nitrox enabled, gas integrated” computer I’d been sent to evaluate, displayed a required stop at three metres for around five minutes. No more than one or two minutes later, my time to surface had jumped from five to 45 minutes! Impossible.

Talking to someone who worked for the manufacturer a few days later, I was told: “if a five or six minute stop is what the decompression algorithm calls for, we pad it… considerably. After all, you must admit if five minutes is good, 45 minutes must be even better…”

It was not necessary to be a rocket scientist, brain surgeon, or hold a PhD in physiology and hyperbaric medicine to work out that thinking about decompression stress in such a simplistic and wrong-headed way was totally bogus. I threw the computer into a junk drawer and went back to trusting a digital bottom-timer and custom tables.

Thankfully, times have changed. Third or fourth generation PDCs — and I am never sure if we are on Gen. 4 or 5 right now — approach the mysteries of decompression stress from a totally different direction. One of informed understanding and regard for best practice.

Diver safety is still paramount, but software engineers seem comfortable following the recommendations of the algorithm loaded into their computers to calculate ascent rate and stops, rather than making stuff up on the fly because a lawyer is breathing down their neck.

Nothing has diluted a diver’s responsibility to understand more about decompression planning than turning on his or her computer. It’s as necessary as ever that every dive team has a robust and sensible bailout plan if Murphy joins them as an uninvited dive buddy.

So where does this leave us?

Well, to begin with, a bunch of the folks who used to eschew dive computers have a different view now in light of those changes; me included.

Nothing has diluted a diver’s responsibility to understand more about decompression planning than turning on his or her computer. It’s as necessary as ever that every dive team has a robust and sensible bailout plan if Murphy joins them as an uninvited dive buddy. And with that in mind, a PDC has now become — for most of us at any rate — the thinking diver’s default tool to keep safe and out of the recompression chamber.

I still teach decompression theory in much the same way as I did in the days of crappy PDCs when they were not worth the real estate they took up on a diver’s wrist.

My dive students need to understand in their own terms my tongue-in-cheek statement that a decompression algorithm is mathematics — a pure science — while physiology is smoke, mirrors, Latin, and alchemy — guesswork, variables and overcomplicated grammar! No disrespect intended towards physiologists, but the complexities of human physiology are not easily captured with mathematical formulas.

Most critically, once they have processed that, it’s important that we accept and are comfortable in the knowledge that we CAN be bent even when our computer says we are not!

Computers, even the very best, are fallible. They will supply the same ascent profile regardless of how we feel the day of our “big dive.” (Or our little one.) A computer doesn’t know that we’re feeling like a piece of toast left out in the rain for the afternoon, or that we got no sleep the night before, after drinking a half-bottle of rum and smoking three cigars.

In essence, divers are kept safe from decompression stress for the most part by statistics and probability, and common sense. And that common sense extends to their choice of which PDC to wear.

Luckily that has become surprisingly simple. We can very easily find one that has a proven track record; that uses a proven algorithm; that has an intuitive way to program variable conservatism levels for different types of diving (and different days) on land and even during a dive; that has a graphical interface showing tissue loading; and that’s easy to read when we need information in a hurry… like when we’re diving. If it also has good customer support, buy it!

There are divers still who believe as I did once, that PDCs have no place in a technical diver’s toolkit; however, times change. And I have a firm belief now that being a Luddite is not only NOT best practice, but it might result in an unwanted chamber ride!

For more information about the author go to https://decodoppler.wordpress.com/

---

Written by Steve Lewis

Steve Lewis is a technical diving instructor trainer, author, and marketing, and training consultant. He thinks of himself as a cave diver, but loves historical shipwrecks. He has written several textbooks and instructor guides. His titles include: The Six Skills and Other Discussions, a guide for technical divers and the very popular Staying Alive: Applying Risk Management to Advanced Scuba Diving.