So how can we improve diving safety?

Gareth Lock is a man on a mission. The 46-year old British technical diver, and retired Royal Air Force senior officer navigator who served as both a senior supervisor and tactical flight instructor on a C-130 flying squadron, and is a certified Kelvin TOP-SET (professional incident investigation) senior investigator, wants to bring aviation’s rich body of knowledge of human factors and their impact on safety and performance, to the sport diving industry. Since beginning his PhD examining the role of human factors in scuba diving incidents in 2012, Lock has published numerous articles in magazines and scientific journals on the subject and presented at nine international diving conferences.

In 2016, he launched a high performance “Human Factors Skills in Diving” educational program to improve divers’ knowledge, skills and safety. The program includes an online course suitable for all divers, and a classroom course aimed at instructors, instructor trainers and those undertaking higher risk diving such as technical divers and cave divers.

Over the last two years he has personally trained more than 150 divers in five countries in human factors methodology including the senior staff from the Global Underwater Explorers (GUE), International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers (IANTD), National Association of Underwater Instructors (NAUI), and Scuba Schools International (SSI), the National Park Service Submerged Resources Centre dive team, and 30+ diving safety officers during the annual American Academy of Underwater Sciences (AAUS) conference. He was also recently appointed the Director of Risk Management for GUE.

I caught up with Lock earlier this year at the Long Beach Scuba Show where he was giving a presentation. Here’s what the man had to say.

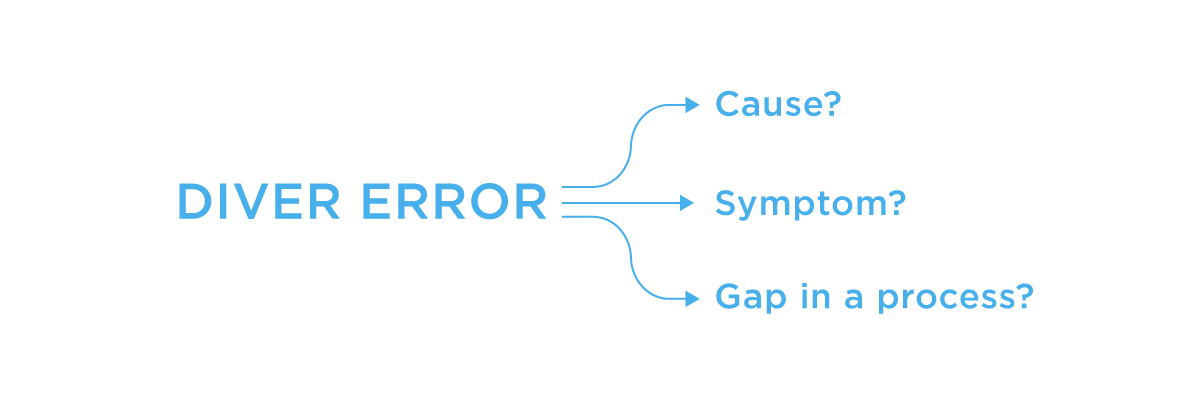

Menduno: I was intrigued by the title of your talk: “Why Human Error is a Poor Term If We are To Improve Diver Safety.” Maybe you could explain why that’s the case.

Gareth Lock: The reason why I put the presentation together is because we often see in accident reports or summary pieces that the prime reason for the accident or the death was diver error. It’s such a general term that could mean three areas: the error could be the cause, it could be a symptom or it could be an outcome or a gap that's in a process. And none of those actually help us understand how it made sense for the individuals in question to do what they did?

It’s also used for diver shaming i.e. we don't need to look further at this incident because it was the diver’s fault.

Yeah, that's it. Listing human or diver error in an accident investigation is a copout because it means that you don't have to go digging. You don't have to ask those awkward questions. However, from my perspective, a fatality is a really poor way of learning because the majority of accidents come down to poor decisions, which are apparent in hindsight and usually the decision-makers are dead. Near misses are far more important to look at, in my opinion, than fatalities. There are thousands of near misses every year and these can provide a great learning opportunity.

We have the ability to learn from near misses and accidents in aviation because we have data collection: the black box that looks at the flight envelope; the aircraft, what it was doing, the switches, the controls. We also have cockpit voice recorders so we can pick up what the verbalized decision-making process was, so we can re-create the story and determine what the thought process was.

Unfortunately, in diving, we usually don't have the ability to re-create the thought processes of the diver, and even though the dive may have involved rebreathers, many of which have data collection devices, we’re not usually able to determine how it made sense to the diver to do what they did.

What would be an example of an incident that was classified as “diver error” that caused us to miss the important bits?

An example I use in my online course concerns a diver who ran out of gas on an air dive to 60m/200ft and despite having a buddy next to him, he made a bolt for the surface and subsequently died as he missed 30-40 minutes of accelerated decompression.

It is easy to focus on the proximal cause of an accident i.e. the diver ran out of gas. The important question is why did they run out of gas. Just saying they weren’t paying attention doesn’t help fix the problem because unless we find out why they weren’t paying attention, the issues will remain. Was it distraction, task loading, expectation based on previous experiences (they could be used to shallow water diving and the incident involved a much deeper dive than normal), what was it?

In this case, as with nearly all accidents, there were multiple factors that combined and resulted in the accident. These included goal oriented diving, task fixation and narcosis while on the dive leading to reduced situational awareness, ineffective team diving skills—the diver did not use his team mate when he ran out of gas and poor communications between the team and the skipper. The dive plan was also changed multiple times while on the bottom which led to confusion within the team, and the diver failed to use available resources such as gas from his team mate’s spare cylinder to lift the artefact they were after, which led to his own gas supply being compromised.

There were many factors involved.

Accidents and near-misses usually result from a number of factors, some of which appear to be irrelevant at the time or their consequences are not fully realised and many of them occur in a non-linear fashion so there isn’t necessarily the ‘chain of events’ which is often talked about.

We can only identify the factors by creating a context-rich story, one in which all of the positives and negatives are discussed, and that includes talking about the ‘rules,’ which were broken. It’s about getting to a level of granularity that can add value in terms of taking preventable actions next time.

Just saying that a diver ran out of gas and that was the triggering event, doesn't get you a lot. What do you do, tell the diver ”Ok, next time don’t run out of gas.” Yeah great, thanks! Because I was really planning to go diving and get injured or kill myself next time.

What is Human Factors and Ergonomics?

What you are saying is you have to get to the specific underlying factors?

Yes. We need to understand their local rationality; how it made sense for a diver to do what they did given the information, skills and knowledge they had, combined with the relevant social factors. Those factors might be peer pressure, normalisation of deviance, time pressure, fear of challenging their instructor, not understanding the briefing or the equipment or social conformance. Many people think that divers who have accidents or near misses “choose” to act recklessly, and yet the socio-technical system they are part of might not be helping them make good decisions.

So what do we do?

There are two parts to human factors analysis in diving accidents and incidents. One is developing quantitative metrics to identify where the problems are. Part of the challenge there is that that we need a common taxonomy of human factors (and other contributory factors) that can be used in accident analysis across multiple datasets. In fact that is the subject of my PhD thesis.

The other part is the qualitative side, the narrative, which I'm really more interested in. It’s encouraging people to tell the stories about how and why their actions made sense to them at the time.

If you get people to tell their story about what happened on a dive using a specific debrief framework, it helps them to realize, “Oh, that was important. I didn’t know to look for that. That was a trigger point for something that happened. Brilliant.”

Now they’ve got a mental model that they can run simulations against about what's going to happen. But if you hadn’t done that, they wouldn't know what to look for the next time. People don’t spot outcomes when it comes to prevention they spot cues or clues, which they know will lead to an adverse event. Prediction is a much better skill to develop than prevention and/or mitigation.

So that's the bigger piece, creating an environment, a culture, where we are able to tell our story without fear of people throwing rocks at us for being human and subsequently making mistakes. A poor “Just Culture” isn’t just an issue in diving; healthcare, another area I work in, suffers massively from this problem where mistakes are often hidden for fear of litigation.

"We need to recognize we are all fallible and that most people do not aim to create an unsafe situation. Having a Just Culture makes it possible for us to learn from our mistakes."

So we need to create a “Just Culture” within the diving community if we want to improve safety?

Absolutely. It’s having the psychological safety where I can say what happened and you're not going to have a go at me for being stupid or making a mistake, and I'm not going to feel scared to put my hand up if I think something isn’t right. We need to recognize we are all fallible and that most people do not aim to create an unsafe situation. Having a Just Culture makes it possible for us to learn from our mistakes.We seem to have developed a culture of blame in diving. Anytime there is an accident people go crazy with blaming and shaming. Why do you think that is?

I think there are a number of reasons behind it. First is our tendency for something called the fundamental attribution error. This is a huge bias, which leads us to blame individuals, or ‘things’, rather than look at the circumstances involved and try to understand why people did what they did.

Second, we engage in “difference by distancing,” i.e. we try to find differences in what someone did compared to what we would do, because “we would never make such a mistake.”

Third, there is the effect of litigation in our society that says that someone must be responsible for the accident, rather than building a story about how the accident came about. Society has a tendency to reduce personal responsibility and therefore we try to push against this and for people to take more personal responsibility and manage their own risks. Yet how do you manage risks if the prevalence of outcomes (especially near-misses) is not known?

Finally, there is the prevalent “fear of failure” that cuts across our society. Failure is seen as wrong rather than an opportunity to learn. This begs the question, is an incident or accident investigation about learning to prevent it from happening again, or is it about blaming someone as the research shows that these two are almost mutually exclusive.

As an example of the massive challenges faced, I know that one agency has written at the top of their incident report forms: “This form is being prepared in the event of litigation.” How truthful, open and context-rich do you think such an account is going to be for learning and not blaming?

So how do we move to a more Just Culture?

How we move forward is both really simple and difficult at the same time. The simple part is to ask the question “How did it make sense for the diver(s) to do what they did?” If instead you ask, “Why did it make sense?” you are implying judgment. By looking at the “how” we can identify more contributory factors than just “what happened”.

In addition, we need to start talking about failure and human error in our training programs and provide context-rich case studies, which dig into the human factors rather than brush them off with “diver error.” Instructors can really aid this process by talking about the mistakes and errors they have personally made as part of each and every dive debrief showing that they are fallible. At the same time, incident and accident investigations need to turn from blame and protectionism towards learning from failure.

You are also pushing in this direction with your courses.

Yes, I am addressing this by running both online and face-to-face classes, which look at human factors, human error and Just Culture. The online class provides the basic concepts of the theory and then analyzing an incident in detail, highlighting the contributory factors and how the incident was emergent. The face-to-face classes take this to another level where I discuss the theory in more detail and then use computer-based simulations (which have nothing to do with diving by the way) to show that failure is normal and the only way to improve is through robust and reflective debriefs where we show fallibility in a safe environment.

"It is easy to blame an individual for failing, but when many of the failures are systemic in nature, it requires organisations to be introspective and has been shown in many other domains, organisations don’t like to do that."

What would say are the biggest obstacles to change?

The biggest obstacles are cultural, both at the societal level and at the diving community level. Diving, especially technical diving has a reputation for being driven by the negative side of ego where we are often unable to question or challenge someone for something we consider unsafe.

My opinion is that one of the reasons for the slow change is because it is easy to blame an individual for failing, but when many of the failures are systemic in nature, it requires organisations to be introspective and has been shown in many other domains, organisations don’t like to do that.

Some of the training agencies are supportive of my efforts, some say they already teach this (which is not true) and some say that it doesn’t meet with the aims or objectives.

What can we do as individuals?

Stop and think before you jump to criticize someone. While speculation can help develop potential hypotheses about why something happened saying, “He should have…” or “The rules say…” or “I was taught to…” means you are applying hindsight bias. You know what the outcome was, so you can now look for clues and cues, which you know from hindsight, are relevant to the situation, instead of putting yourself in the diver’s position and trying to understand how it made sense for him or her at the time.

In addition, be upfront and honest about your own mistakes and failures and treat them as opportunities to learn. Just think, you don’t shout at toddlers when they are learning to walk and keep falling over, so why should adults be any different when it comes to learning from failure in diving?

More information see: http://www.humanfactors.academy

---

Written by Michael Menduno

Michael Menduno is an award winning reporter and technologist who has written about diving and diving technology for more than 25 years and coined the term “technical diving.” He was the founder and publisher of "aquaCORPS: The Journal for Technical Diving" (1990-1996), which helped usher technical diving into the mainstream of sports diving, and organized the first Tek, EUROTek and AsiaTek conferences, and Rebreather Forums 1 & 2.